Basics of Strength Training- Part 2

HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH?

Let’s geek into repetitions, sets, and frequency of training

When we ask ourselves or others about training, we usually wonder:

How often should I exercise?

How many rounds of this and that?

How many repetitions of each exercise?

If you are already exercising, you’ve probably found yourself counting how many more times you’ve got to do a movement for the set to be over, hehe 😊

In terms of how many times a week we should be doing weight training, as mentioned in the first section of this article, the recommendation by the WHO is 2 to 3 sessions a week.

This is for the general population; this is something that applies to everyone.

However, if you are a powerlifter or pro athlete, your number of sessions will vary, as will the type of training you get every session.

Powerlifters and people preparing for a competition can easily train 5 or 6 times a week, splitting what muscle groups they target every day to keep the volume in check.

A professional pole athlete can do 3 times of gym training, so to speak, plus 3 or 4 pole sessions during the week, which are also a form of strength training.

A mum busy with her job/business and kids can do 2 sessions a week and that will be enough for her and her lifestyle.

See what you can fit into your life that aligns with your goals and go with that!

What matters most when it comes to how much we should train is total volume.

Volume equals the amount of work performed. It is how much loading we get, and how many stimulating repetitions every time we do an exercise.

So, what’s all this?

With loading, I mean mechanical loading: this is the actual stimulus that drives muscle growth. Stimulating reps are all the repetitions you do that drive muscle growth. To drive muscle growth, what we know so far is that we need to get enough load (weight) and repetitions to get us close to failure.

So, volume is calculated based on the number of working sets we perform throughout the week for each muscle group.

And working sets are the ones that we do with a load and number of reps that take us near failure.

I know, I’ve said this twice already. And it’s on purpose.

Notice I say CLOSE to failure. Not to failure.

Close to failure is when suddenly the speed of our movements starts to slow down, when we start feeling it, and it starts to get hard. But we can still complete that rep. And maybe a few more. But we don´t.

We stop short of failure when we notice those “symptoms”. And that is considered to be the sweet spot in the most recent literature.

Why short of failure and not complete failure?

Let’s say you are doing a biceps curl with a 10kg dumbbell. You are doing 3 sets of 10 repetitions. Every set, when you get to number 9, you start to find it challenging to continue. But you can still do that full rep and 1 more in good form. That is close to failure. Anything within 5 reps to failure is considered a working set. That will allow us to reap the benefits of the work and also recover in time for our next session.

Now, let’s say you’re doing the same exercise, the same weight and the same number of sets and reps. However, when you get to 9 or 10, you feel the weight so heavy that you cannot physically complete those reps at all. So, we must stop there. You’ll still get through the session, but it will most likely take you longer to recover for your next training of the same muscles.

I went down a tangent there so back to the original question, HOW MUCH IS ENOUGH?

Do as much as you can while still being able to recover and improve.

We don’t want to do so little that we keep training and get nothing of it (improvements) or too much that we cannot improve due to fatigue.

Just to wrap up this section, you may be wondering what is best: many reps and low weight? Or fewer reps and more weight?

In terms of performing working, stimulating sets like we discussed above, there is virtually no difference. Research has shown that anything between 5 and 30 reps per set will become a stimulating set if we take it close to failure.

Regarding the number of sets per muscle group per week, the general recommendation is 10 to 20 working sets.

But remember, IT’S ALL RELATIVE. Not 2 people are the same. We have to consider aspects such as training history, how much stress you can take, nutrition, sleep, and what sorts of sets you are doing.

Start low and work your way up. Let’s say you are heating up a cup of coffee in the microwave. You wouldn’t set a 3-minute timer right away. You’d probably start at 30 seconds, check the coffee, and add some more time if needed.

The same happens with training. Set, reps, number of sessions per week. It all varies from person to person.

So, again: start slow and work your way up. Prioritize good quality and technique in the movement, rather than volume, especially in the beginning. And be mindful not to increase all variables at the same time.

Once you get familiar with the equipment and technique, you can start adding weight, or sets, or repetitions. We’ll learn more about this in the next section 😊

In the meantime, you can continue geeking out in this article by ASCM: The New Approach to Training Volume • Stronger by Science

HOW DO WE PROGRESS?

This can a be tricky but also very simple question to answer.

We have to consider 2 main aspects:

When to progress

How to progress

1. When we think of the when part of the equation, how do we know when we can make any changes to a workout routine to make it more effective?

Surely, we will be a bit bored of doing the same workout after 3 or 4 weeks. But boredom is not the best indication that something needs to change. When it comes to strength training, unfortunately for a lot of us, repetition is key. The more reps we put on for each muscle group, the better results we will get.

However, there’s a catch: remember in the previous section we discussed volume? Doing 50 push-ups a day (chapeau to those who can manage that) is a lot of reps. But not necessarily, a lot of results. If you can comfortably do 50 push-ups a day and fully recover in 24hs, then you’re certainly not working close to failure and doing enough stimulating sets.

We could say that comfortably doing the number of reps and sets indicated using the current load (weight), something you used to find challenging and used to be able to take close to failure in those parameters before, is a good indicator that a change is needed.

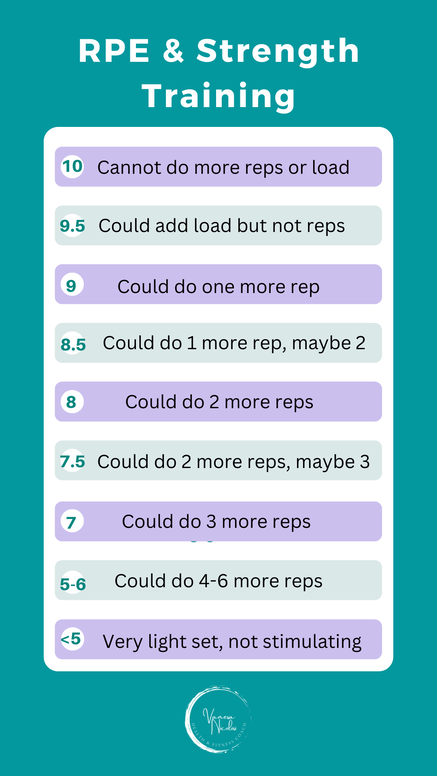

Introducing: RPE

RPE is the Rate of Perceived Exertion, meaning how do you feel when doing a certain exercise? Is it challenging enough? Can you get to the last rep and feel you’re getting fatigued and close to failure? Or is it too challenging and you cannot complete the last 2 or 3 reps at all? And on the other side of the spectrum: is it so easy that you could do more than 5 repetitions in addition to what you are doing? Is it so not challenging that you don’t feel like you’re putting in any effort?

Let’s make it visual, shall we? If you Google the RPE scale, you’ll find many images, most charts related to cardiovascular levels of effort. This is valid. But we got a great RPE scale (thanks to Luke Tulloch) for what each number represents in strength training.

2. Now, to answer the HOW of the progression questions.

And the queen of all principles of exercise is Progressive overload:

When we talk about training, we are implying there is a goal behind our sessions, ideally, we have a program to follow, and we are making notes every session to be able to see our progress. Otherwise, it is simply exercise.

Mind you, exercise is very much needed, and in no way should it be undermined. You have and will continue to hear me say that movement is key to a good quality of life. And exercise of any kind is the number one hack to a longer, healthier one.

However, if you have a specific goal in mind in terms of strength, hypertrophy, and endurance, then you will need a program to follow and a way to track your progress. And that is training.

Training of any kind follows certain principles, like that of specificity, meaning it has to be specific to the individual and their goals; or reversibility, which means pretty much “use it or lose it” (if you stop training, the progress you made can be reversed)

When it comes to progress and adapting a program, the key, however, is the principle of progressive overload-

Overload refers to:

Intensity

Frequency

Time (duration) and

Type of training

In order to progress, we will put our bodies under stress with training, and this stress or overload can be achieved by playing with any of those variables.

We call it progressive overload because we cannot modify all the variables at one given point of the program and expect good things to happen. If we tweak it all, we will end up failing at the exercises and not progressing.

Instead, we will want to increase the stress or load gradually as we progress in our training. The increase can be achieved by adding more weight, changing the tempo of an exercise (for instance instead of going down to a squat at the usual speed, we can go down in 1,2,3 hold 1 second down, and then come up) or adding more sets or reps, for example.

So, let’s say at the start of your program (week 1-day 1) you are doing 10 split squats with no added weight and that feels like an 8 or 8.5 on our RPE scale.

By week 4, you do your set of split squats and realize these 10 reps are feeling more like a 7 on the RPE scale. In other words, it feels easier to do this exercise in this manner. The following week, we will want to switch up this exercise a bit to make it more challenging for you again and get you back on your 8 or so of RPE.

Here’s is when progressive overload comes into play. How can you make this exercise more challenging?

You could add weight, maybe carry one 4 kg dumbbell on each hand.

You could also add a pause at the bottom of the squat, increasing the time under tension. Go down, pause 3 seconds, then come up.

You could as well increase the number of repetitions from 10 to 12 or 15.

You could make them more explosive or even change the exercise to a different, more challenging type of squat, like a Bulgarian.

But you cannot make all these changes at once.

For the exercise to continue being effective, you’ll want to change just one thing. Choose one and stick to that for a couple of weeks. When it gets easy again, you can make another change in any one of the variables mentioned before.

If you change too many things at once, you’re more likely to get overworked and take longer to recover.

So progressive overload is just that: making progressive changes to continue getting stimulating sets and reps.

Circling back to the boring repetitive programs, we can always add more and play with the different variables to ensure maximum effectiveness as we include variability.

I love this passage from an article in Stronger by Science:

More is More • Stronger by Science

If you want to get stronger, the best thing you can do is train more, provided you’re sleeping enough, managing stress, and have good technique.

Sure, other factors certainly matter. And sure, it’s certainly possible (though unlikely) to overtrain. But in the simplest terms possible, your current program is probably less effective than it would be if you just added an extra couple of sets to each exercise. If you’re not making progress, your default thought shouldn’t simply be, “time to find an exciting new program!” It should be either “time to add more work to my current program” or time to seek out a new program that employs more volume than my current one.”

REST AND RECOVERY

If you’ve followed the How Much and Making Progress sections, then, I bet you can find the answer yourself to this last question:

How often do I train and how much recovery time do I need?

And yes. Of course: it’s all relative 😊 The answer we all love and hate.

But that is real life for most of us.

We know that, ideally, we would do 2 to 3 sessions a week of strength training per se. That leaves at least 4 days in the week to rest and recover. So, we may have 1 or 2 days in between each strength training session.

Now, when it comes to rest and recovery, we have more than one option on what to do or not to do.

Maybe you hear rest is for the weak. Or No pain, no gain. Or even a rest day is a lost day

From my experience, it is quite the contrary.

No rest can lead to over training, and this in turn leads to no progress

Too much pain can get us over-stressed and give us zero or very little gains

A rest day might be just the one thing we need to start seeing those results.

Before we go on, a personal story:

Last week, I spent a full week weighting myself every day (you don’t have to, I do it because I love data), and every day it was the same: not a single gram lost. I knew I was training properly following my program. I had gone a bit off track with my nutrition but not as much as not to see any progress at all. It was one day, and the rest of my week was on point. And then, Friday night came. I went to bed at around 11 pm. Woke up on Saturday at 9.30 am (a very rare thing for me, as I usually wake up at 7ish in the morning). Did my toilette routine and stepped onto the scale: I had “lost” 1 kilo.

The moral of the story: the weight reflected the previous week was not real. It was a product of bloating and stress, plus some extra food. One good night’s rest set me back on track.

Back to you. Progress towards your goal and having a healthier lifestyle include Recovery and Rest. These are crucial to seeing gains, physical and emotional.

When it comes to organizing your training, you can decide to give yourself a full break from exercise in between the strength training sessions.

Or you can choose to do a cardio session that day: run, jog, brisk walk, swim, bike, or dance. Whatever you prefer. Anything that elevates your heart rate, and you can keep up for 30 to 60 minutes.

You can also choose to do some active recovery, like gentle stretching, some soft yoga, or having a massage or spa day.

So, a training week could look something like this (just one idea)

Day 1: Strength Training at the gym. Full Body

Day 2: Salsa Class

Day 3: Simply rest (from purposeful physical activity)

Day 4: Strength Training at the gym. Full Body

Day 5: Yoga

Day 6: Brisk walk for 45 minutes

Day 7: Full Rest

When we consider getting healthier and developing healthy habits, we tend to focus on food and exercise first. And that is great. They are both important factors for our overall health and aging.

But we must remember that sleep and rest are key components. If we don’t recover properly, we will have a harder time seeing results. Plus, when we don’t sleep well, we tend to eat more, move less, and be overall more stressed. This will affect our mental health and, thus, our physical health.